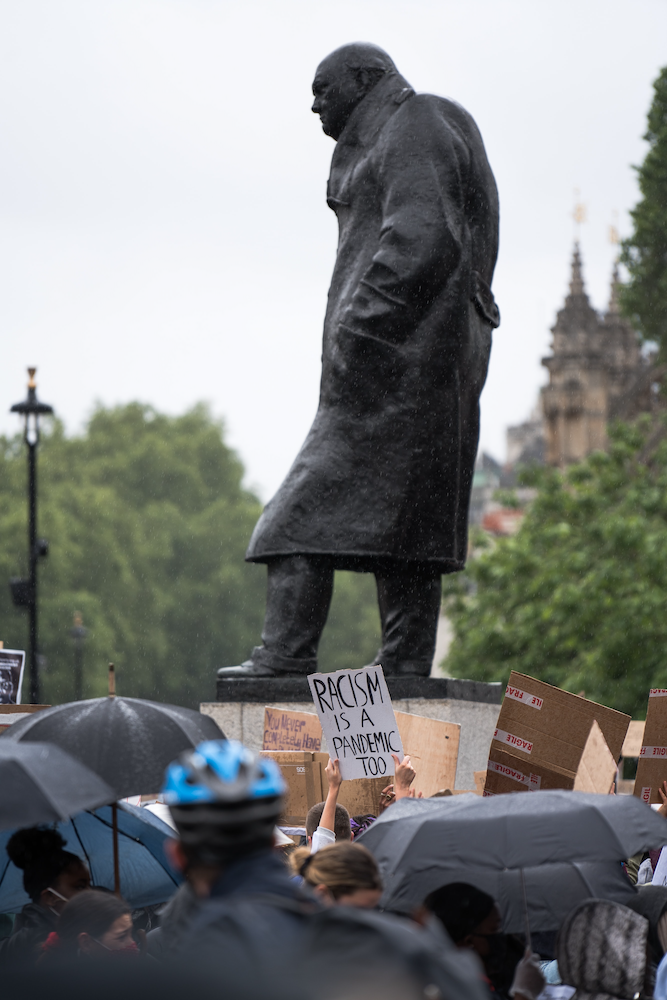

❝No one pretends that democracy is perfect or all wise. Indeed, it has been said that democracy is the worst form of Government except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time❞ Winston Churchill famously declared in 1947.

In 2021, the world watched as a fragile democracy in Afghanistan propped up for twenty years by Western democratic countries crumbled before its eyes. Only months before, media outlets ran headlines about the storming of the Capitol – the symbol of American democracy – in the country which De Tocqueville wrote so famously about almost 200 years earlier. In Europe’s own backyard, there has been ample evidence of democratic backsliding and so-called illiberal forms of democracy brewing in regions where it was so emphatically embraced only three decades before. There are loud debates over how elections and referenda have been meddled with by undemocratic forces in what were once called ‘mature’ democracies. It seems like everywhere we turn, talk about the undermining of democratic values or the need to reassert them are underway, as if the banal has suddenly become preciously rare – the rule of law, protection of minorities, tripartite division of powers, individual rights, and transparent procedures and institutions.

While democracy has been touted as Europe’s most precious legacy, it is also a notoriously conflicting concept, offering no easy definitions. At its root is the tension between classical liberalism, with its focus on individual liberties on one hand, and democratic theory based on the common good on the other, in what Chantal Mouffe calls the democratic paradox. What theory of justice and ideals of freedom are highlighted at each end? Are women and men free only when they enter the polis and work for the common good, or are they truly free whilst pursuing their own self-interests? How does this tension play out in contemporary contexts? This issue was none too clear at the height of the Covid pandemic, where individual liberties seemed to clash with the responsibility to act collectively for the common good.

If the root of this is the tension between individualism and the common good, then at the heart of democracy is the demos, or people, or demoi, peoples. Again, we come to conflicting definitions of who the people are and the boundaries of their belonging. Rogers Brubaker reveals at least three core meanings: the people as the common or ordinary people, or the ‘plebs’; the sovereign people, or the ‘demos’; and to the culturally or ethnically distinct people, or the nation or ethnos (Brubaker 2017). The boundaries in which the people are located – be it local, national, or supranational – provide the framework for the implementation of kratos, or power, laws, and institutions that ensure civil equality and the access to political rights and participation.

The making of those rules by the people, a plural, heterogeneous collection of individuals, is faced with yet another conundrum – how to reach a consensus. According to the contemporary political theorist Giovanni Sartori, the one thing we need to agree upon in a democracy is how we will disagree – through the framework of institutions and procedural consensus. Enter the public sphere.

Now, however, even these building blocks are crumbling under the weight of polarisation, populism, and fragmentation. In John Erik Fossum’s view, while some differentiation is needed to prevent concentrations of power, to balance majority views with the protection of minorities, and to provide citizens (and non-citizens) with access to rights and recognition, sometimes treating them differently in order to treat them equally, too much differentiation leads to various bias, unaccountability and, ultimately, to various forms of dominance.

Yet where there is dominance there is resistance, and new forms of participatory practices, bottom up and horizontal activism, localised community-building projects, a revival of the concept of the Commons, are flourishing, and a (still) new and ever changing medium, the virtual space, is showing both its power and potential at building (and breaking) democratic ideals. New and old media are co-creating and refracting the language of political discourse as if through a glass darkly, the broken mirror that is at once an eye opener and catalyst for change, or harbinger of disinformation and disruption.

This year’s Euroculture Intensive Programme on Dissonant Democracy aims to critically examine the fundamental questions that are at the heart of what Europe has taken for granted and what seems to be unravelling far too quickly and without much resistance. What are the pillars of democratic values in contemporary Europe and how are they (not) being safeguarded? Who are the people, or the demos, to be ruled, and to rule in turn? Who is to be represented and how? Who funds democracy? How are information, disinformation and misinformation discursively constructed and what implications does this have for the proper functioning of democracy? How may new forms of participatory practices help to shape and redefine what democracy is in the 21st century?

In a first subtheme, (Un)democratic Frameworks, Procedures and Institutions, we make room for exploration of the political, philosophical and legal frameworks of democracy, from historical perspectives on its rise (and fall), through the roads to (un)freedom, to the current debates on constitutional models of democratic functioning of the European Union (federalist, intergovernmentalist, cosmopolitan). In pluralist societies and larger entities like the EU, should we speak rather of demoicracy – the multifaceted governance of peoples, rather than just one people? Under what conditions can deliberative democracy, as outlined by Habermas, be exercised and at what scales of governance? What role does Europe play in exporting democratic values abroad – otherwise known as the use of soft power – and what benefits does it bring, to whom, and at what price? Can democracy be hegemonic?

We invite students to contemplate the frameworks for democratic functioning, under what conditions they are effective, transparent and reflective of principles of democracy and, conversely, under what conditions they falter. What happens when electoral frameworks are slightly redrawn, just enough for gerrymandering to occur and turn representative democracy into a game of electoral calculations? How are the scales of democracies organised at local, national, supranational and cosmopolitan levels, and how much differentiation can these levels sustain before democratic principles turn hegemonic? How do these different levels of democracy impact on citizens’ rights and access to participation? How are borders constructed around them, defining the Others, the foreigners, denizens, those who do not belong? Who are the minorities, how are they protected, othered, ignored or undermined? How is political consensus forged? Importantly, what checks and balances are necessary for the rule of law and what happens when the demos, the people, overrule those structures and principles? How can we unpack the oxymoron of illiberal democracy? Students are asked to take empirical examples through the use of case studies, comparative analyses, political / policy analysis, historical sources and other social science approaches and apply the appropriate methods to critically analyse their significance for contemporary Europe in a globalised context.

The second subtheme, (Un)Democratic Identities, Discourses and Public Spheres, we tackle the ways in which democracy is discursively constructed, twisted, refracted through language, media, literature, social platforms and new forms of communication. Here we focus on the one hand on mediums – the vehicles – of (un)democratic processes, reflecting on their nature and power to sway votes, identities, attitudes and allegiances. What role do (social) media play in the spread of (mis)information and how does this have an effect on the functioning of democracies? The spread of democratic values or the stirring of old fears, xenophobia, and allure of safety in an age of increasing insecurity? We welcome students to explore the meaning of discourses, the use of tools of persuasion, and to critically assess the media through which information passes and spreads. Next, what images are spread by these vehicles, what utopias/dystopias are we drawn to, what underpins them and how do they reflect our current state and societal fears? Why, all of a sudden, are dystopian Black Mirror genres at the top of the charts, played out in the likes of the Squid Game and Handmaid’s Tale? Lastly, we focus here on intersecting identities like gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity and religion, amongst others, caught up in struggles for recognition, redistribution of resources and, increasingly, used as scapegoats for the ills of contemporary liberal society. How are these identities reflected, represented and framed in public debates and media platforms? Under what conditions are they instrumentalised and used to orchestrate moral panic?

Students may employ discourse analysis, media studies perspectives, netnography, visual analyses and more to ascertain the power and significance of communication, language, discourses and narratives and how they are used and reflected in (un)democratic processes.

In the third subtheme, (Un)democratic Mobilisations and Participation, we investigate participatory practices that mobilise people to act and react, to come together in communities with a purpose, to revolt and dissent against forms of power and oppression. Co-designing local communities, empowering marginalised groups, engaging in democratic life, encouraging youth activism and creating a sense of belonging in an age of isolation, political apathy and individualism – how does it work and under what conditions? What is the role of dissent in democratic processes? What forms of e-democracy can help or hinder participatory practices? In this subtheme we encourage students to observe people – individuals, groups – and the governing structures in place that focus on action and mobilisation, keys to democratic processes. Are all forms of mobilisation for the common good of democracy? What new participatory practices can we observe? What fora, projects, calls to action have the power to move groups, or whole populations to action? Through sociological, anthropological and other social science perspectives, students are encouraged to collect empirical data around them – in populations, social movements, actions and projects for democracy-building, and the sometimes reactionary counter-movements accompanying them. Foucault reminds us that where there is dominance there is always resistance, although sometimes it is not quite clear who is being dominated, and who is resisting.